Whitwick Historical Group has regularly posted articles in the monthly “Community Voice” magazine which is delivered free to homes in the Whitwick, Thringstone, Swannington, Coleorton and Coleorton Moor areas. Here you can revisit articles that you may have missed or wished that you had kept. For those living further afield, these will possibly be entirely new to you.

January 2019

Keeping Warm

The prospect of a dark, cold January sparked reminisces amongst the team at the Old Station about how we kept warm in the decades before homes had central heating, when open coal fires were the norm.

Unlike a radiator, a brightly burning coal fire has an effect on almost all our senses. Many of us will have sat looking into a fire and imagining all sorts of pictures amongst the flames, burning coal and embers. Once it is dark, without a light on in a room, the firelight creates constantly moving images, patterns and shadows against the walls, furniture and curtains.

Usually, you can hear a coal fire. It crackles and even roars as it burns. There is a particular smell also, especially from the smoke. Naturally, we feel the warmth too. In fact the only sense which a coal fire does not usually affect is taste.

It is always tempting to romanticise the past and we need to remind ourselves that traditional coal fires involved a lot of hard work. Apart from dealing with the ashes and dust, open fires need to be watched and guarded. Regularly, someone has to stop what they are doing, go outside to the coal-house or bunker and bring in more coal for the fire. It is difficult to control the heat. Many readers will remember waiting for the fire to burn well before a room was warm. There was no instant heat at the turn of a dial.

This month’s photograph from the late 1970’s, which is used by kind permission of Mr. C. Matchett, shows another issue and a scene that was once familiar. On this winter’s day, a load of concessionary coke has been left on the pavement for the family to carry into their fuel store.

On the other hand, having an open fire meant that you could toast bread on a toasting fork. Such a simple thing delivered a very special taste as butter melted into the warm bread, a taste that no electric toaster can reproduce. Readers who lived through the 1940’s and 1950’s will recall cooking with coal on a range or grate. A kettle always rested on a trivet over the flames. Baking and roasting were done in the oven at the side so that a great deal of experience was needed to cook a meal.

Whilst living rooms were generally warm and cosy, the rest of the house could be, and often was, cold. Frost on the inside of bedroom windows was not unusual as you woke up on a winter morning. “Jack Frost has been!” was the call as the intricate patterns were revealed behind the bedroom curtains. Extra blankets were piled on the beds and hot water bottles placed between the sheets. Some older houses had fireplaces in bedrooms. These were seldom used by most families unless someone was ill.

No matter what cold, damp weather this January brings, thankfully we will be warm inside our homes. We will have the central heating switched on. It will have been programmed to give heat as and when we need it. We can use all our rooms in comfort and sleep beneath our lightweight duvets. Yet, when we walk into any building that has an open fire, it has an immense attraction and we find ourselves drawn towards it.

The coal fire is long gone at the Old Station but we like to think that a warm welcome awaits all members and visitors. On behalf of the Committee and volunteers, Happy New Year.

February 2019

Quarrying in Whitwick – Early History

What do these local buildings have in common: Grace Dieu Priory; the Man Within Compass pub (aka The Rag & Mop); the dam wall of Blackbrook Reservoir and Mount St. Bernard Abbey? The answer is that they were all built with Whitwick stone, the theme of this month’s article from Whitwick Historical Group. The photograph from our archive shows a remarkable scene taken in Whitwick’s Forest Rock Quarry. It’s caption refers to the 150 ton stone which reputedly was the largest single block excavated in any know quarry at that time (1911).

Quarrying is one of our oldest industries and still a very significant aspect of Leicestershire’s economy. Archeologists have shown that stone from Charnwood Forest has been used for over 6,000 years. About 4,500 B.C. local rocks, most probably collected from the surface of the ground, were fashioned into polished axe-heads. There is evidence that the Romans used Charnwood stone too.

Local rocks are ideal for construction purposes and the production of crushed stone, known as aggregates, because they are so hard. The rocks are amongst the oldest in Britain, over six hundred million years old, and were formed when molten magma from island volcanoes cooled and solidified. Today we see these distinctive rocks around us in the rocky outcrops in our landscape and the countless miles of dry stone walls as well as in buildings. The rock has a grey colour but closer inspection reveals a variety of other shades, especially when the rock is wet.

There are no active quarries in Whitwick now but readers will be aware of the huge Peldar Tor Quarry by Leicester Road, headquarters of Midland Quarry Products Limited. Yet, the first village quarries were located elsewhere. Two important quarries were in Cademan Street, one on each side of the road; another was close to Grace Dieu Road at Carr Hill. Smaller sites can be identified in the rugged area north of the village.

The development of large scale quarrying in Whitwick was prompted by the increased demand for better highways in the nineteenth century. Crushed stone was constantly required for road building, repair and improvement (as it is today). In 1893, the Whitwick Granite Company was established by local businessmen and, initially, forty men were employed at Forest Rock Quarry north of Leicester Road. We can only imagine how strenuous and back-breaking the work was since there were few machines. Some of the workers in the photograph look very young and none of them seem to be wearing any protective clothing.

The story of Whitwick’s quarries includes several themes such as transport, technology and environmental concerns and these will be explored in future articles. In the meantime, there is an outstanding collection of quarry photographs at the Old Station which the group is happy to show to interested visitors.

March 2019

Historical Links – Whitwick Farms

Whitwick has a very long history. The village is first recorded as “Witewic” in the Doomsday Book in 1086. This name is a combination of two Old English words, “Wite” comes from the word “Hwit” which means “white” or “Hwita”, a man’s name. “Wic” means a farm, usually a dairy farm. So this gives us either “the dairy farm of Hwita” or “the white dairy farm”. Either way, farm is significant and is the focus of this month’s article from Whitwick Historical Group.

No one can deny the importance of heavy industry and manufacturing in Whitwick’s story but farming has played a key role too. Within living memory, there were farms right in the very centre of the village: Hall Farm and Church Farm. The photograph from the archives at the Old Station, shows two young ladies standing by Hall Farm in the 1930’s. On the left is Sarah Moore, a milkmaid, and on the right, Lizzie Paton Berrington. The Berrington family owned the farm at that time. The original Hall Farm was built about 1350 and was sited where Whitwick Methodist Church now stands, at the Market Place end of Hall Lane. The main entrance was close to the Old Vicarage in Silver Street (now Silver Oaks Residential Care Home). Whitwick’s cinema was built on the front field of Hall Farm in 1914. Land belonging to Hall Farm was on the south side of Hall Lane. The farmhouse was demolished as recently as 1971.

The farmhouse of Church Farm is now No.2 Vicarage Street. Road alterations in 1973 cut through the farmyard. A large barn stood between the yard and the narrow entrance to Hall Lane and gave the name “Barn End” to the village end of Hall Lane. For many years, Church Farm belonged to the Jarvis family and their fields were on the north side of Hall Lane. Until farm land on both sides of Hall Lane was sold for housing development, dairy cows were walked from the fields to the milking parlours at Church Farm and Hall Farm twice each day at different times, meaning four journeys by each herd. Hall Lane was a narrow thoroughfare; this must have been a cause of congestion.

Earlier, other village farms included Bonnett’s Farm which was also known as the Fee or Free Farm. This was located at the entrance to the Hermitage Leisure Centre car park and owned by the Bonnett family for about three hundred years. Much of the land belonging to this farm was sold off for development of brick yards. Readers may be surprised to learn that The White Horse pub in the Market Place was originally a farm with land towards Silver Street.

Faming was labour-intensive in the past and many people researching their family history discover that “ag lab” (agricultural labourer or farm worker) is an employment description on census records. The farms in and around Whitwick were mixed farms raising livestock and cultivating cereals, vegetables and fodder crops. The work would have been hard and demanding with long hours and little protection from bad weather.

Although highly mechanised today, farming remains an industry which is fundamentally linked to the seasons. As spring arrives, it will be easy to spot farmers becoming increasingly busy in their fields as they have been for centuries. Information about the many other farms in Whitwick, such as Glebe Farm and Spring Hill Farm, can be researched at the Old Station where WHG volunteers would be delighted to see photographs or artifacts related to local farms.

April 2019

Whitwick’s Silver Street – Serving the Local Community

A chance remark by a visitor to the Old Station led to this month’s article from Whitwick Historical Group. Our visitor had been told that not so very long ago, Whitwick residents could buy all they needed for everyday life without leaving the village. Confident that this was correct, we decided to search for evidence and “Kelly’s Directory” for 1935 was the place to look.

Kelly’s Directories are a vital source of information. For each settlement there is a descriptive passage followed by a list of prominent inhabitants for the year in question and information on all commercial activities. It is this last resource which gives an invaluable “snapshot” of manufacturing, commerce, public buildings and services. One of Whitwick’s main thoroughfares, Silver Street, was selected. The results confirmed our initial thoughts and astounded the team of volunteers.

In addition to the Picture House, Dr Prys-Jones’ Surgery, Whitwick Constitutional Club, The King’s Arms public house and the branch of Coalville Working Men’s Co-operative Society Ltd, there were twenty-six businesses in Silver Street in 1935. These included: three fried fish dealers; three shops where boots and shoes were sold and repaired; two hairdressers; two butchers; one baker; one greengrocer and one wheelwright and undertaker. Five “shopkeepers” are recorded along with a grocer, a fruiter, a beer retailer and, intriguingly, a “marine store dealer”. Businesses providing a service included a painter, a dairyman, a music teacher and a carter. Interestingly, eight of the twenty-six businesses were owned by women.

Shops were closed on Wednesday afternoons and, as a general rule, no shops opened on Sundays. Otherwise, Silver Street must have been extremely busy. No ordinary homes had fridges or freezers so food shopping had to be done more frequently than is usual today. Now we can buy almost anything at a supermarket; a shopping trip in the 1930s would have involved calling at a variety of shops to buy all that was needed. Inside the shops, customers were served by staff from behind a counter and the choice of goods available would seem very limited to modern shoppers.

Older readers will recall some of the Silver Street business proprietors’ names such as Aris, Baxter, Briers, Greasley, Haslegrave, O’Meara, Pegg & Sons, Toon, Vesty and West. It is likely that families were loyal to individual businesses and, being regular customers, would mean the possibility of chat or even the exchange of gossip during the transactions.

This month’s photograph from our archive shows a view of Silver Street from the Market Place end. It was taken in the 1950s but several shops can still be seen. On the left-hand side, the name “O’Meara” is visible on the wall of the second shop and the barber’s striped pole is in place at Greasley’s hairdresser shop. Both the photograph and “Kelly’s Directory” gave WHG volunteers an opening for sharing pleasant memories of a vanished era.

If this type of local social history is appealing and you would like to browse through the trade directories or have your own memories or photographs, the team at the Old Station would be delighted to meet you.

May 2019

Whitwick Park – A Special Asset

Whitwick Park on North Street is one of Whitwick’s most pleasant assets. The photograph, taken during an afternoon last month, shows the Park being used by people of all ages. Like so many local features, the Park has its own interesting story which Whitwick Historical Group is pleased to share with the wider community.

Before Whitwick Park was laid out as we recognise it now, there was a sports field next to Church Lane. At least two very successful football teams and one cricket team played on the field, often attracting large crowds. In the early 1930’s, discussions began between the Whitwick Colliery Welfare Fund, Coalville Urban District Council and James Shipstone & Sons, the brewery that owned both the Duke of Newcastle Hotel on North Street and the land behind it, with the aim of providing a park for the village.

By 1936, everything was settled for the creation of two tennis courts, a bowling green; park area with seats, children’s swings and slides; access with an entrance. Flower beds and trees were planted later.

Sixty-six years ago, in May 1953, there was another significant development in the story of the Park. Whitwick Park was officially named as a “King George V Field”. A King George Field is a public open space “used for the purpose of outdoor games, sports and pastimes” dedicated to the memory of King George V, in 1936, after the King’s death, the King George’s Fields Foundation (KGFF) was set up to promote and assist the establishment of playing fields for the use and enjoyment of the people, a marvelous living memorial. Since 1965, all the King George Playing Fields have been legally protected by “Fields in Trust” and managed locally, in Whitwick’s case by Whitwick Parish Council.

Throughout the UK, 471 King George V Fields were established. The stone panels on the pillars either side of the Park entrance identify the park as one of this special group. All the parks nationwide which were supported by the KGFF have the same panels designed by George Kruger Gray; on the left, a lion holding a royal shield and, on the right, a unicorn holds a similar shield. Look out for the panels as you pass by or go into the Park.

Whitwick Park is a resource to be treasured and used well. Readers may be interested to learn that one group very closely linked to the Park, the Whitwick Park Bowls Club, is celebrating its 75th Anniversary this year. Whitwick Historical Group sends congratulations to them and best wishes to everyone who enjoys this village amenity.

June 2019

Framework Knitting – A Cottage Industry

Researching family history is a constant and fascinating activity at Whitwick Historical Group and using census returns is a primary source of information. With families who have a heritage based in the East Midlands, the occupation of “Framework Knitter” is often given on the census records. This is not surprising since, in Leicestershire alone, as well as the city of Leicester, 150 towns and villages had framework knitters in the first half of the nineteenth century. One of these villages was Whitwick. Before the local collieries and later factories provided employment, framework knitting was a dominant industry.

What is framework knitting? The knitting frame was invented by William Lee in 1589 and was hardly changed over the decades. It enabled knitted goods, particularly stockings or hose, to be knitted many times faster than by hand. The photograph shows how the knitter sits to operate the frame manually. A high level of skill, considerable physical effort and good eyesight were needed. Most framework knitters but not all, were men. A flat piece of fabric was produced which was then seamed by hand. Significantly, framework knitting took place in people’s homes or in a small “frame shop” or outbuilding, hence the term “a cottage industry”.

The history of framework knitting is a huge topic and this article will focus on just one aspect. By the 1840s, it is thought that there were over four hundred knitting frames in Whitwick and knitters were struggling to make a living. Throughout the area, prices for completed articles had fallen drastically whilst frame rents had increased. Very few knitters owned their own frames. They had to cover the cost of replacement needles, seaming and getting the goods to the warehouse of the master hosier for whom they worked, often in Loughborough. Working hours were twelve to fourteen hours per day and frequently involved all family members including young children.

In 1844, a Commission of Enquiry was set up to investigate working and living conditions. Thirteen knitters from Whitwick gave evidence along with three master hosiers, shopkeepers and the Anglican curate. One shocking disclosure was that in some cases wages were paid not in cash but in goods. Joseph Sheffield, a framework knitter of Leicester Road, stated that one of his rented frames was worked by a woman who earnt seven shillings a dozen for stockings but only received one shilling in cash. The balance was paid in goods from the master hosier’s shop.

Whitwick Historical Group holds a copy of all the evidence collected by the Commission in Whitwick, Thringstone and Osgathorpe at the Old Station. It gives a poignant insight into how so many of our ancestors lived. It may be that one of your forebears was interviewed by the Commissioners. The report is particularly valuable since little other evidence of this once vital industry remains. If you would like to learn more or have your own family history research to share, the volunteers at WHG will be pleased to see you.

July 2019

19th July 1919 – Peace Day

Last year we commemorated the centenary of the signing of the Armistice in November 1918 which marked the end of fighting on the Western Front. However, it was the Treaty of Versailles, signed in June 1919 that marked the end of the Great War. To celebrate this a Bank Holiday was declared in Britain. It was on 19th July and was known as “Peace Day”.

Although the main spectacle was in London, other celebrations took place in cities, towns and villages across the country. Naturally, one such village was Whitwick. One of the team at Whitwick Historical Group has researched how the festivities were reported locally. What follows is adapted from an article in the Coalville Times published on 25th July 1919. “Peace Day” was celebrated here in true Whitwick style. Not for many a long day have the fine old bells rang out from the ancient church tower as they did during Saturday afternoon. A full peal of 5,040 was rung in 2 hours 55 minutes by eight ringers.

The photograph from the archive held by Whitwick Historical Group shows the Parish Church tower and the War Memorial which was unveiled in 1921 and records the names of 82 men who had lost their lives in WWI.

We can surmise that the village must have been decorated as the article goes on: “The decorations were very effective. The first prize went to Messrs. Briers and Bonser (Leicester Road), the second to Mr Squires (Three Crowns Hotel), and the third to Mr George West (Conservative Club). Suitable mottoes were displayed at numerous points and there were many flags flying.”

Other activities included a procession of ex-servicemen, children and Scouts which was led by the Whitwick Holy Cross Band. At the head was carried a laurel wreath round the words, “Lest we forget,” as a tribute to the fallen. There was a tea for the children that took place in the Range Field off Silver Street. The old people, discharged and demobilised soldiers and sailors, Scouts, bell-ringers, and the Band had their tea in the National School in the Market Place. There must have been sports during the day too since we can read that the sports prizes were presented in the evening by the Rev. Walters and Father O’Reilly. The report concludes by stating: “There was a capital response to the appeal for funds, the cost of the proceedings being met by voluntary contributions.”

A century on, reading the newspaper account, it seems that the whole village must have been involved in making Peace Day a very special occasion. No doubt, it was a bitter-sweet event for many families and we know that there were hardships to come but during that July day the focus of the community was on festivities, celebration and thankfulness that the War was indeed over.

August 2019

Spring Hill – A Well-Loved Spot

When chatting about the long school summer holidays, it is not long before people of a certain age begin to reminisce about how they used to play outside as children and visit local beauty spots with their families. A well-loved place in Whitwick was Spring Hill, to the north of Leicester Road. It is always spoken of in affectionate terms.

Spring Hill had typical Charnwood Forest scenery with jagged rocky outcrops, dry stone walls, small trees and bracken. Its beauty attracted visitors not just from Whitwick but from much further afield. Local families walked to Spring Hill along Leicester Road and climbed the steep steps on the footpath. Visitors from elsewhere came by bicycle or bus. It was a wonderful place to play, explore and just relax. Another appeal was that bilberries grew there and could be gathered and taken home, although purple stains around mouths revealed that some berries had a far shorter journey.

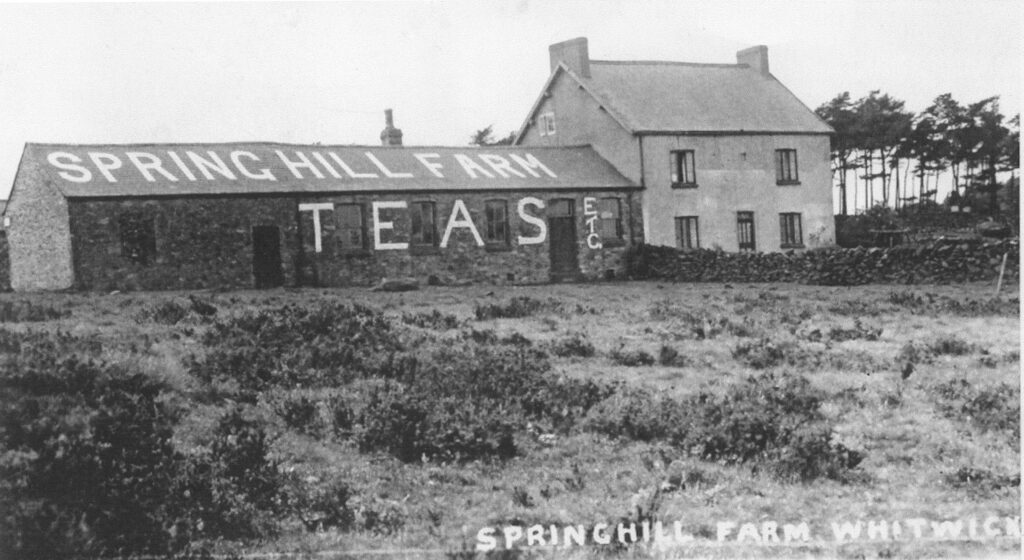

This month’s photograph from the archive at Whitwick Historical Group shows the farm that was on Spring Hill. The advert for “Teas” is unmissable and will bring back memories amongst older readers. The tea room had Biblical quotations on its walls and wooden beams. Although the farm and tea room look rather desolate on the photograph, in earlier years much fun, laughter and general merriment had taken place there. It enjoyed its heyday between the two World Wars and was the venue for many excursions and Sunday School outings when games and sports took place. At weekends and Bank Holidays, an ice-cream van parked at the farm too. Visiting Spring Hill was both an accessible and affordable treat and a regular outing for many.

Eventually, the tea room was closed due to public health legislation although the farm itself remained for some years. It was the development and expansion of quarrying in Whitwick that resulted in the loss of much of Spring Hill and the farm. Quarrying near Spring Hill had begun in the 1890s; during the 1920s Spring Hill Farm and other parcels of land were purchased by Whitwick Granite Company. As the line of rock extraction moved to the north and east, the former agricultural and recreational landscape was lost.

The summers of our childhood often seem to be made up of carefree play in fields and woods. In the 1950s, children would set off after breakfast and be outside for hours. We climbed and tumbled out of trees, paddled and fell into brooks, built dens and knew where to find blackberries. If you have photographs taken on Spring Hill or elsewhere in the countryside around Whitwick from previous decades, the volunteers at WHG would be delighted to see them and share your memories.

September 2019

Whitwick Imperial Football Club – Leicestershire Champions

“Football” has been chosen as this month’s article from Whitwick Historical Group as the start of this 2019-2020 league season has a special historical significance. One hundred years ago, the 1919-1920 season kicked off on Saturday 30th August 1919. This was 1,584 days after the last league match since national league games had been suspended in 1916.

In Whitwick, the 1919/20 season was to bring outstanding success to the most senior team in the village: Whitwick Imperial Football Club (aka The Imps). Formed at the start of the 1908/09 season, they played their first league football in the Coalville and District League where they finished champions at their first attempt. The move into the Leicestershire League in the following season proved challenging due to stiffer opposition. Yet, after some mediocre results, they finished as league runners-up in 1913/14.

At the same time, the Imps had enjoyed some success in local cup competitions. They reached the final of the Coalville Charity Cup in both 1912 and 1914, losing the former.

The Imps were winners in the 1914 final when they beat Coalville Town by 2 – 1. This game was played on the Fox and Goose ground in Coalville and drew an attendance of 6,000 spectators. More successes followed until league and cup competitions were suspended due to WW1.

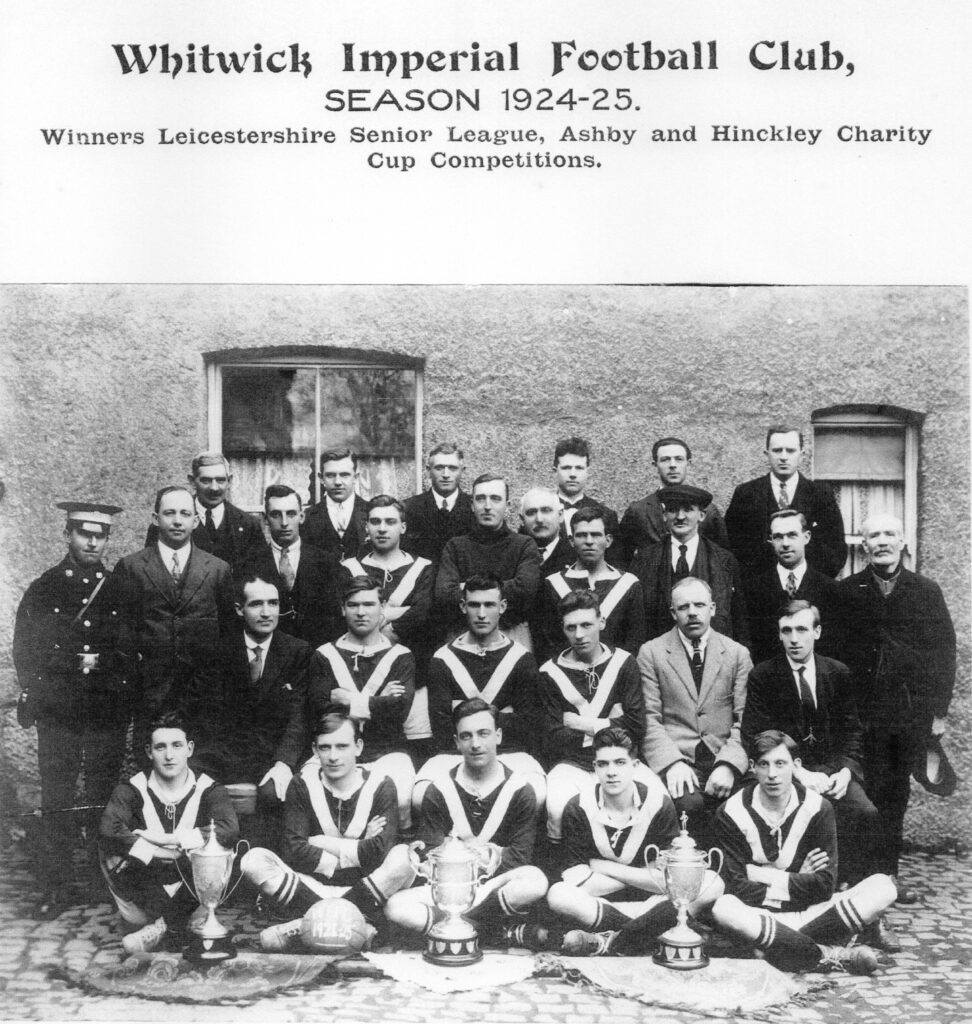

From the season which began 100 years ago, the talented Imps enjoyed a remarkable run of success. They dominated not only Whitwick football but the rest of Leicestershire too. During the next six seasons, this skilful village team were Leicestershire League Champions four times. The photograph shows the proud players and officials at the end of the 1924/25 season with their trophies.

This golden period saw the Imps flourish in cup competitions too. They were runners-up in both 1921/22 and 1922/23 in the prestigious county-wide Senior Cup. Both finals were played on the Leicester City ground at Filbert Street. The Imps were beaten narrowly each time by Loughborough Corinthians, their arch rivals. The club felt strong enough to enter the FA Cup during these years with mixed results. Meanwhile, the Coalville Cup games continued with many exciting games. The people of Whitwick were richly entertained by this fine side on their Duke of Newcastle ground, now Whitwick Park.

Moreover, it was in Whitwick Park, earlier this year during a guided walk, that WHG received a very generous donation: two medals awarded to the Imps for the seasons 1919/20 and 1924/25. They had belonged to the Club Secretary, shown in the photograph, whose descendants wanted the medals to remain in the village. The Group was delighted to accept the medals which are now on display in the Old Station. In addition, thanks to the enthusiastic and thorough research by a WHG member, we also hold more information about Whitwick Imperial Football Club and other very successful village teams. During this month the Group is participating in “Hello Heritage” when volunteers will be happy to welcome visitors to the Station to look at our collections linked to football and many other topics.

September 2019

Whitwick – A Safe Haven

Just over eighty years ago, a large number of children from Birmingham arrived in Whitwick. They were evacuees. They knew nothing about Whitwick, what they would be doing in the village or when they would be going home. No doubt they were anxious, fearful and already homesick. They were amongst the 75,000 children evacuated from Birmingham to Leicestershire. This month’s photograph, taken close to Whitwick, shows evacuees from English Martyrs School in Birmingham who were billeted in the village.

In the first four days of September 1939, nearly three million people were transported from towns and cities in danger from enemy bombers to places of safety in the countryside. It was the biggest mass movement of people in Britain’s history. Most were school children, who had been labelled like pieces of luggage, separated from their parents and accompanied by their teachers. Those who arrived in Whitwick had come from five schools in Birmingham and were to continue their education at the two village schools.

Parents had been issued with a list detailing what their children should bring with them. It included: gas mask in case; a change of clothes; a warm coat and food rations. The departure from Birmingham seems to have been well organised but the finding of hosts and homes for the children in Whitwick was more testing. One evacuee recalled later “I was evacuated from English Martyrs School together with three sisters and a brother and recall waiting in the hall at Holy Cross, the last of the children to be chosen due to the fact that Mummy had told us to stick together. Finally Mrs Moore of the Constitutional Club in Silver Street took pity on us and took us four girls, while my brother, Peter was whisked off forlornly to a billet in Cademan Street.” One wonders how well anyone slept that night, either in Birmingham or Whitwick.

Log books from the two village schools record how the sudden influx of children was dealt with. Holy Cross School had eighty-seven evacuees with their teachers when the school opened for the new school-year. Four classrooms and the hall were placed at their disposal but the log states: “They have little or no equipment and seating is lacking. I hope both will soon be at hand.” A similar number of evacuee children attended the National School in the Market Place; some of these had their lessons in rooms at the Conservative Club in Silver Street. Thinking back to our own schooldays, readers can probably imagine what upsets and scuffles happened at playtime as all the children had to adjust to the unprecedented situation.

By the end of the month, the anticipated bombing of Britain’s cities had not happened. Some parents came from Birmingham and took their children home. Evacuation, however, continued and some children settled so well in the village that they never returned to Birmingham. This heart-warming sentiment was printed in a Birmingham paper: “Evacuation has shown that there are a great many kind people in the world and that Whitwick has a large share of them.” The volunteers at Whitwick Historical Group would be delighted to hear any evacuee-related stories or see photographs from those challenging times.

November 2019

The Pride of the Forest

When we are not discussing the decidedly autumnal weather, travelling and traffic seem to be up there as a perpetual topic of conversation at the moment. Road works, lane closures, route diversions and the ever-increasing amount of vehicles on our roads are a constant theme of our chats at the Old Station and undoubtedly elsewhere. Thinking about a less congested age prompted this month’s article from Whitwick Historical Group.

The photograph, which was donated to WHG by Mrs M Partridge, features an image from an era when roads were less overcrowded and almost everyone depended upon public transport. It shows one of the buses from the “Pride of the Forest” fleet, a Whitwick-based bus company. The driver, Charles Thomas Mann (generally known as Tom Mann), is the owner of the company and the conductor with the ticket machine is Mr Birkin. Readers familiar with vintage vehicles will recognise that the bus is from Guy Motors of Wolverhampton, an innovative passenger vehicle manufacturer.

The story of Tom Mann and “Pride of the Forest” begins in the early 1920s when Tom and his wife Winifred (aka Winnie) started the bus company. Their base was at the Black Horse pub in Church Lane Whitwick where Winnie’s widowed mother was tenant landlady. In the 1920s buses had become the predominant form of public transport, replacing horse-drawn vehicles and, locally, passenger trains. People travelled by bus to work, for routine expeditions such as shopping, and for social activities. The Manns’ first bus, known as “Little Bus”, was eventually followed by others to give a fleet of seven. There were regular services operating between Coalville, Shepshed, Loughborough and Leicester. Of special interest is that Winnie was the first female bus driver in Leicestershire.

Moreover, Thringstone-born Tom Mann has a remarkable history. Before he and Winnie began the “Pride of the Forest” company, he had endured many horrifying experiences. In WWI, he was sent from France to the Balkans. Here he had to cope with escaping over mountains to Albania whilst existing on very little food. He managed to reach Corfu by means of a rowing boat and was repatriated to recover.

Tom was sent back to France and the Somme where he was wounded, suffered from the effects of mustard gas and shell-shock. After lying in a shell-hole for three days, he was rescued and treated in hospitals in France, Leicester and Broom Leys but he had lost his hearing. He was discharged from the army as medically unfit for further service in 1918. Tom was only twenty-one years old. He and Winnie married later that year.

As a successful bus operator, Tom Mann became Chairman of the East Midlands Motor Omnibus Proprietors Association. Whilst holding this position, he presented a clock which was mounted in Shepshed Bull Ring. He retired in 1934. The “Pride of the Forest” business and its route operating licences were sold to Midland Red.

In an age of multi-car families, it is difficult to imagine the impact that small local transport companies had on improving lifestyles for ordinary people not that many decades ago. If you would like to look at more similar images or share some of your own, please call in at the Old Station where volunteers will be happy to see you.

December 2019

A Tale of Names, Past and Present

Volunteers at Whitwick Historical Group recently spotted a piece of card which had fallen out of one of our books. What was printed on the card made us all smile. It was “Recitation on Public House Signs in Coalville Urban District & Thringstone.” Many years ago someone had written a story that included most of the names of pubs in the local area.

This prompted us to think about Whitwick and its pubs. The village has been famous, or infamous, for its large number of pubs and licensed premises and here is our attempt at a story using many of their names.

“I was taking a walk through the village when whom should I spot coming out of The Hastings Arms Hotel but The Duke of Newcastle and The Marquis of Granby. They invited me to join them on a visit to The Prince of Wales and The Lady Jane who were staying at The Castle. Naturally, I was delighted to do so.

We entered the castle through a grand archway where The Kings Arms were carved into the stonework. Inside the grounds there was activity everywhere. The Joiners in particular were working hard. Looking up, I saw through a window in The Belfry, a Crown and Cushion. This puzzled me because last time I was there, I spotted Three Crowns.

However, there was no time to linger. The Marquis was keen to look at a White Horse that was for sale at The Hermitage Hotel. Making our excuses, he and I set off. On our way we noticed The Cricketers practising behind The Abbey. Their shouts had disturbed the animals in the nearby fields. I could see a Bull’s Head through a gap in the hedge. He looked very agitated and so did some Foresters who were trapped behind him.

Walking on we were overtaken by a Waggon and Horses with The Beaumont Arms painted on the side. A Black Horse was being led on a long rope behind the wagon. We asked what was going on and were told that the horse only had Three Horseshoes. Apparently the horse had stumbled over a Forest Rock. He was being taken to the stables at The Railway Hotel to wait for The Blacksmiths.

All these delays meant that the Marquis missed his chance with white horse. It had been bought by The Duke of York, a keen sportsman and admirer of The Hare and Hounds. The Marquis was furious and threw his Boot at the Duke. The Duke did not retaliate but offered the Marquis a small box. Inside was the strangest object: a disc showing a Man Within The Compass. I suggested we all retire to The Talbot Arms to mull over all the events of the day and enjoy a well-deserved drink.”

Readers will spot that Whitwick’s Clubs and some pubs have not been included and for this we apologise. Moreover, they may feel that they could compose a far better story using the names available. It would be wonderful to see some of these at the Old Station. One opportunity to bring them along would be during our Open Afternoon on 12th December 2019 (1pm – 4pm; free event). If you would like more information on village pubs, the WHG publication “Ale Houses of Whitwick” by C Matchett gives a fully illustrated and comprehensive account.