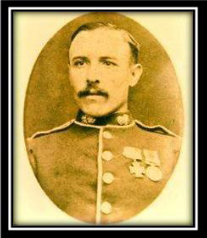

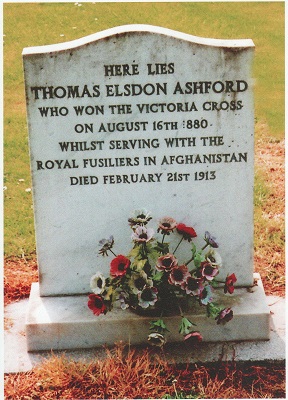

Thomas Elsdon Ashford, V.C.

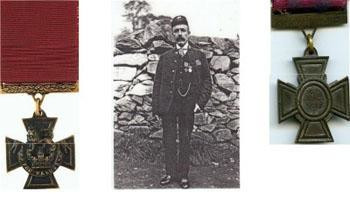

Shown here with kind permission of Colin Bowes-Crick Major (Retd), Royal Fusiliers Museum, Tower of London

It is over a century since the death of Thomas Elsdon Ashford, V.C. Here is recorded the story behind the man who was awarded the Victoria Cross and other associated information that has been gathered from a variety of sources including books, newspapers and the internet. These sources and acknowledgements are listed at the end. Thomas was born in 1858 at 2 Peck’s Cottage, All Saints, Newmarket, Cambridgeshire, the illegitimate son of Thomas Ashford, a boot maker and Emma Elsdon. The 1861 census shows Thomas as being aged 2 along with his twin brother, John and both carrying the surname Elsdon. In 1861 his parents married, but his mother died in 1869 and his father later remarried the same year.

General Roberts

Thomas joined the Army at Woolwich for the 49th Brigade on 12th June 1877 and joined the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Royal Fusiliers on the 14th June. His records show him registered as a Baker, aged 18 years and 6 months, with his height being 5 feet, 5 inches, a 34 inch chest, brown hair and hazel eyes. He was assigned the regimental number 49/1317. In November, 1879 he was sent to Bombay and then dispatched to Kandahar four months later.

The 2nd Battalion had been in India since November 1873 and had been on garrison duty in several towns until they were ordered to march into Afghanistan in February 1880 as part of the British invasion under General Roberts V.C.

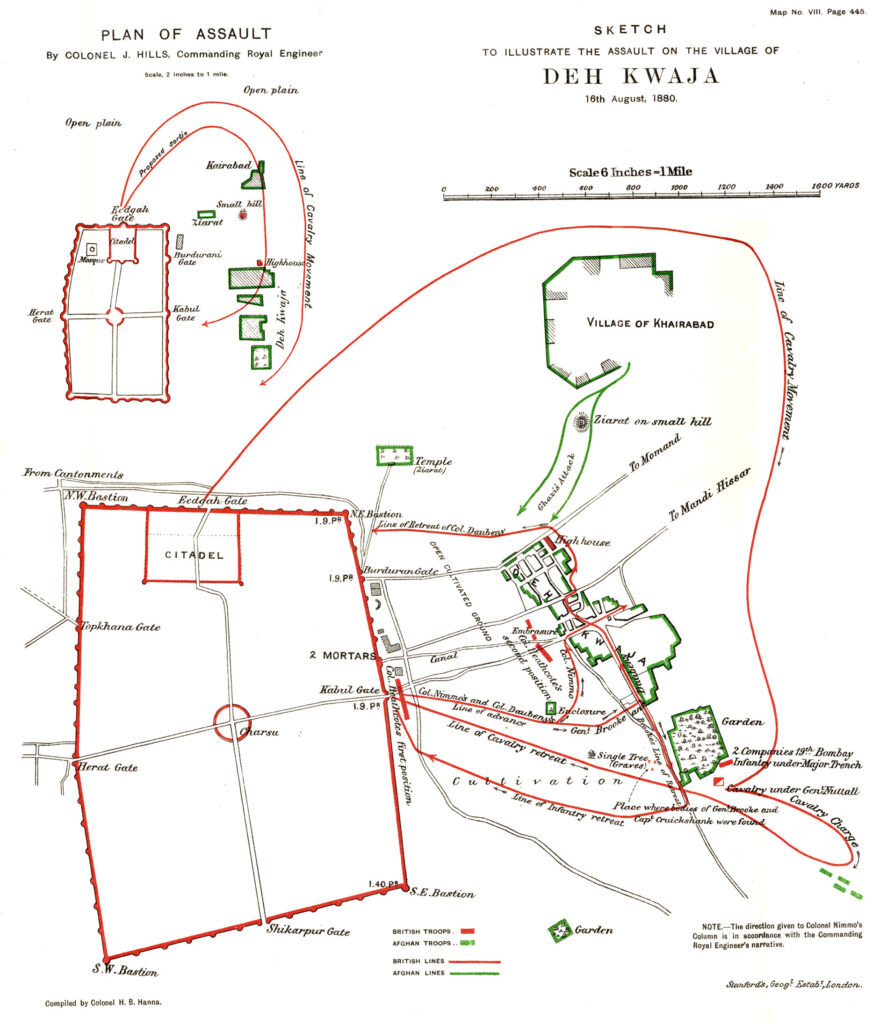

They arrived at Kandahar on April 26th. On August 11th, the 2nd Battalion of Royal Fusiliers and 4,500 other British and Native troops were besieged by 10,000 enemy tribesmen. On August 16th, the Fusiliers took part in an attack on a nearby village called Deh Khoja. Both sides suffered heavy casualties, with British forces losing 200 men, 22 of which were from the Royal Fusiliers and the British were forced to withdraw.

The official record, reported in the Western Times on October 26th, 1880 as follows:

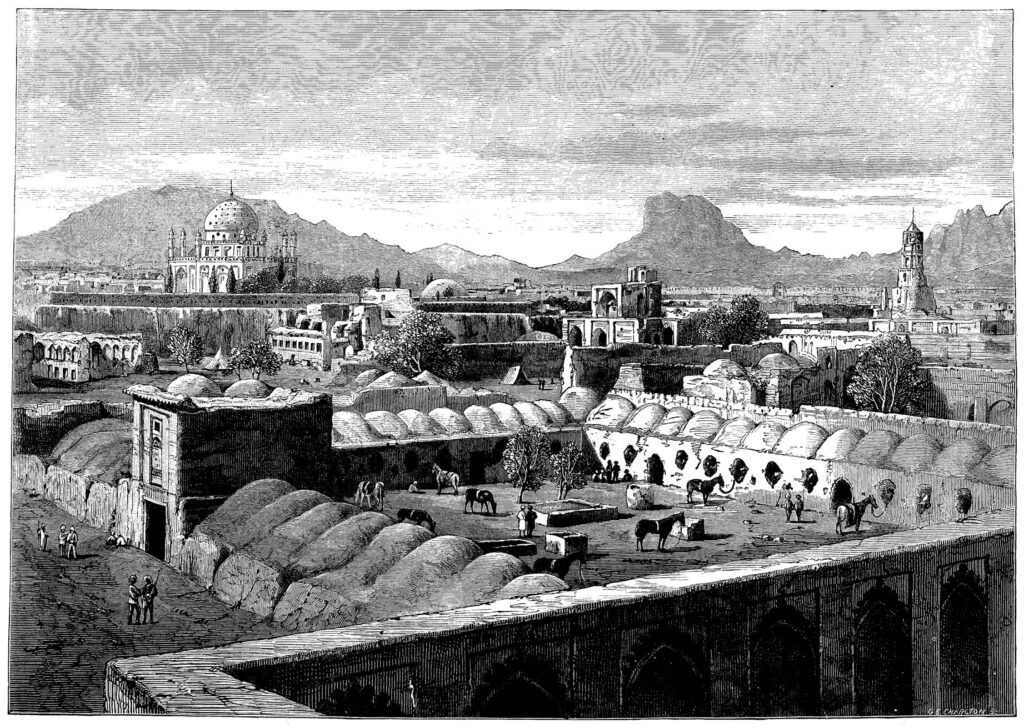

“Following the news of the disaster at Maiwand, General Primrose, in conference with General Brooke, a movement into the citadel of Kandahar was determined upon. The reasons for this step were that the cantonment was indefensible; the water supply was easily divertable; the city, unless seized, would be in a state of anarchy; and no help was to be expected from the Wali, who, in a private interview, strongly advised a retirement from Candahar. General Brooke was despatched on the Kokaran road towards Sinjuri to help in the stragglers. On his return at dusk the withdrawal was completed. The Pathans and disaffected folk were turned out of the city. The effective force within the city was 4,630 officers and men, with 12 guns and two mortars. Elaborate details are given of the steps taken to fortify the city.

The enemy first opened fire on a piquet on a hill, on August 8th on the citadel, and shortly afterwards on the city from the Deh Khorja and Deh Kuttu villages. The fire, though sustained for days, did little harm. The reason for the sortie of the 16th August was in consequence of the intention of the enemy to completely invest the city. They had already occupied and fortified the adjacent villages. The enemy carried on the work at night. There was no indication, therefore, of the position of masked batteries, nor the disposition of a hostile force. A sortie was thus rendered necessary in order to make the enemy show his hand. The plan was to bombard the village of Deh Khoja heavily, and then put the infantry in action, though the distance of the village from the Cabul gate was 950 yards. The chief reasons for the choice of a village out of supporting distance were that Ayoob’s army intercepted the main road, which General Phayre’s relieving force would take, and it was necessary to discover the whereabouts of Ayoob’s 30 guns, two Armstrongs only having opened fire up to that date. The force composing the sortie consisted of four companies of the 7th Fusiliers, eight companies of Native Infantry, and 300 sabres. The cavalry were supported by three guns and two mortars.

General Brooke, who was in command, divided the force into three columns. Orders were issued that the first column should take the road to the right after leaving the Kabul gate, and attack the south village; the second column was to follow the first and take up a position on the right of the first column. Both columns were to advance in open order. The third column was held reserve within the Cabul gate. The cavalry, under General Nuttall, were to issue from the Eedgah gate, and operate against the east and south villages. The guns opened fire at a quarter to five in the morning. The infantry debouched from the Kabul gate at five o’clock, and entered the south village under a heavy fire at half-past five. The Ghazis, who were hurrying across the plain to the assistance of the village, were charged by a troop of cavalry under Major Geohegan and driven back with heavy loss. A second attempt of the Ghazis was stopped by the infantry, and they dispersed. The cavalry again charged them under General Nuttall. On reforming after the charge, General Nuttall received a note from General Brooke to cover the retirement of the infantry from the south to the Kabul Gate.

The cavalry were therefore withdrawn, and they entered the city by the Kabul gate. They had suffered great loss, receiving the enemy’s fire on a very cramped ground. General Primrose’s intention was that the cavalry should remain in the open plain, charging when the chance offered, and returning by the Eedgah gate. The cavalry being thus withdrawn, the enemy were reinforced and the fighting in the village was very heavy. In spite of the stubborn resistance from behind walls, the first and second columns debouched from the northern end of the village.

At seven o’clock the third column held the ground at the centre of the village until ordered to retire. The firing ceased at a quarter-past seven. The enemy’s loss was heavy, while our loss was eight European officers and 90 men killed, six officers and 97 men wounded. The total loss, including followers, was 223. General Primrose estimates that the sortie resulted in a great success. The morale of the troops was improved, and the overwhelming confidence of the enemy was destroyed. The dread of the word “Ghazi” was dispelled. Ayoob shifted his camp for the Argandab on the 24th. On the 25th only did General Primrose venture to collect and bury our dead left behind from our sortie.”

General Haines’ remarks of General Primrose’s despatch, which are concurred in by the Indian Government, are to the effect that the siege arrangements were good. The abandonment of the cantonment was too precipitate, considering the force under General Primrose. Such an action tended to conform the demoralisation of the troops caused by the imperfect news received of the Maiwand disaster. As to the sortie, General Haines considers the reasons to be unsatisfactory. The details of the operation were well and successfully carried out up to the time of the withdrawal of the troops and the cavalry from the south-side of the village. From this point of General Primrose’s narrative all was confusion, although, from the fact of our dead being left on the field, the troops in returning to the city must have been closely followed by the enemy. The effect of the sortie upon the enemy was too dearly bought. General Primrose has been ordered to forward a copy of the instructions issued to General Brooke for the advance towards Sinjuri on the 28th July, and that officer’s report on his return that day.

Besides the official report more individual and personal accounts were recorded in letters home and diaries. This is an account of the diary entries of Lieutenant C.M. Edwards of the 66th Berkshire Regiment at the siege of Kandahar during August 1880.

8th First shell in Kandahar. One gun silenced. On guard, Edghat Gate evening.

9th Working party under hot fire. Two men of the 7th wounded and five natives. Ayab-Khan said to have 80 scaling ladders ready. Sixty rounds were fired into a deserted village, no one but the powers that be knew the reason why. Guns supposed to be there.

10th A few more shells but no harm done. General Brooke had nightmares and having a mumbling in the stomach, said it was guns moving into position in front of the gates. Turned us all out, not a soul visible as was expected. Topkhana Gate guard.

12th This morning we had 24 shells into us, not one doing the least harm. I buried Pte. Holmes in the morning, having the evening before put Cpl. Evans into his last resting place. My batman, Cunningham, wounded in the arms, poor old fellow. I hope he will get safely over it.

13th Keyse, from the tower, sighted Ayab’s camp and two shells from the 40 pounders’ were put in. This somewhat led him, as they were remarkably well pitched and he returned, but without doing any damage. Had the luxury of a night in bed.

14th Not much going on, a little shelling as usual. I was ordered to assist with 50 men to mount a 40 pound gun on the south west Bastion. This was very tough work and the men did it well too.

15th Same as usual. Was on Topkhana Gate guard and kept till 11 am on the 16th.

16th A party of 300 Sowers and 800 Infantry (Europeans and Natives) went out to attack a village opposite the Kabul and Badurain Gates. This was thought to be lightly held, but sad to say this was not the case. It was strongly fortified and every house loop-holed. We suffered fearfully. 14 officers killed and wounded and about 250 rank and file. I was on top of the Khana Gate and I think we bagged about 16 of the enemy from the Bastion. A gun on Piquet Hill of the enemy was said to be dismantled. A 40 pounder amongst the enemy’s staff must have created great damage and scare. Badurain Gate in the evening, all quiet.

17th All wounded getting on well. At present no news.

18th Sale of Cullean and Roberts effects. I bought a gun and a few other things.

19th My day off, so took long rest. No more news, though lots of rumours floating about. Went out searching.

20th Letter from swell old woman, who says that in the fight the other day there were men of great note killed. About 90 regular troops and a lot of villagers. During the action one of our cavalry regiments was seen by the enemy to disappear and they thought it had gone to Chawan. They were in a tremendous funk and were all night entrenching themselves, expecting us to attack. But what could we do?

21st Gordon’s sale, I bought post horn. Poor Cunningham died.

22nd No news given out. Two letters came in, contents not known. A man shot outside Heart Gate, nothing on him.

23rd Sale of Trenches, Staynor and also Colonel Newport. No news.

24th Deh Khorja quite deserted. We went and buried the dead who were in a frightful condition. Most of them were recognised. Plenty of hay and grain brought in and plenty more there. Ayab-Khan gone.

Chelmsford Chronicle

Friday, November 26th, 1880

A Letter from Afghanistan

Lance-Corporal Galley, of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Fusiliers, writing to his friends residing near Chelmsford, gives some particulars of his experiences during and subsequent to the investment of Kandahar by Ayoub Khan. He says that the English forces were under fire nearly the whole time of the investment, as Ayoub’s troops threw a few shells into the fort every day, and parties of British had daily to go out and destroy the villages near the fort, the enemy firing on them all the while and they losing a number of men, while all night they had to be up on the ramparts. This went on until the 16th August, when Ayoub having placed two guns in the village of Deh Khoja, 800 yards distant, thus firing on the British on three sides, a party of 1,100, including 300 of the 7th Fusiliers, was ordered out to storm the village and capture the guns.

“Our guns,” the writer says, “opened fire on the village at five o’clock, and we were waiting outside ready to charge, but when we got there we found the Afghans quite equal to the occasion. We did not fire until we were within four hundred yards, and then we might as well as fired at a brick wall – they had fortified the place so completely. The enemy then opened fire from their loop-holed walls, and killed a lot of our fellows. The first I saw killed was a man of my own company, who fell shot through the neck. Some of our men got into the village, but were driven back by the heavy fire of the Afghans. We were out about two hours, and I myself fired over a hundred rounds of ammunition. During that time, staying as I did for the most part by a wounded man I saw some of the enemy in the open, and got up and fired two shots at them, but scarcely was I down again when some 40 bullets came whizzing about me, yet I did not notice it much then. There were six killed and seven wounded in my own company in this affair, but thank God I came out of it without a scratch. However, it was the hottest affair I have ever been in, and I have taken part in everything where my regiment has been engaged.”

Eye-witness reports of the actual event for which the Victoria Cross was awarded include a letter written by Lieutenant-Colonel Daubney of the 7th Fusiliers who wrote:

“Thus while holding our ground to cover the retreat of the stragglers or wounded from Deh Khoja, an officer, Lieutenant Chase, was suddenly seen coming towards us from the block-house, with a wounded soldier on his back, and attended by a fusilier. The enemy had also seen him, and turned their fire on him. A few yards and he is down and all thought he was done for. Not so, he only wanted breath, and jumping up, he brought his man in amid a shower of bullets and the cheers of our men.”

Another witness was the Reverend A. G. Cane who said:

“I soon had my attention directed to a man leaving one of the Ziarets with another on his back. He was then, I suppose, about 400 yards off and running as fast as possible towards the walls. There was a fearfully heavy fire directed on him from the villages of Kairabad and Deh Khoja on both sides. After running for about a hundred yards I saw both fall and lie flat on the ground, the bullets all the time striking the ground and raising the dust where they struck all round them. I, of course, was under the impression that they had been hit. Soon, however, I noticed Mr Chase get up again, and again take the man on his back for another stage of the same distance, and again lie down for a rest. Again he got up and carried his burden for a third stage, and again lay down. By this time he had got close to the walls. Only those who saw the terrific fire that was brought to bear on these two coming in can realize how marvellous was their escape untouched. At the time they came in they were almost the only object on which the enemy were directing their fire, as the rest of the fugitives had already reached shelter.”

For this action, Private Thomas Ashford, along with Lieutenant Chase of the Bombay Staff Corps received the Victoria Cross. Seven non-commissioned officers (NCO’s) and privates received the Distinguished Conduct Medal. The siege of Kandahar ended on September 1st 1880 and the 2nd Battalion of Royal Fusiliers garrisoned the town until April 1881 when it returned to India to continue garrisoning duty.

The citation for the award of the Victoria Cross appeared in the London Gazette on October 7th 1881 alongside another conflict in South Africa the year before.

War Office, October 4, 1881

The Queen has been graciously pleased to signify Her intention to confer the decoration of the Victoria Cross upon the undermentioned Officers and Soldier, whose claims have been submitted for Her Majesty’s approval, for their conspicuous gallantry during the recent operations in South Africa (Basutoland), and in Afghanistan, as recorded against their names:-

| Regiment | Names | Acts of Courage for which recommended. |

|---|---|---|

| Cape Mounted Rifle-men | Surgeon–Major Edmund Baron Hartley | For conspicuous gallantry displayed by him in attending the wounded, under fire, at the un-successful attack on Moirosi’s Mountain, in Basutoland, on the 5th June, 1879, and for having proceeded into the open ground, under a heavy fire, and carried in his arms, from an exposed position, Corporal A Jones, of the Cape Mounted Riflemen, who was wounded. While conducting him to a place of safety the Corporal was again wounded. The Surgeon-Major then returned under the severe fire of the enemy in order to dress the wounds of other men of the storming party. |

| Bombay Staff Corps | Lieutenant William St. Lucien Chase | For conspicuous gallantry on the occasion of the sortie from Kandahar, on the 16th August, 1880, against the village of Deh Khoja, in having rescued and carried for a distance of over 200 yards, under the fire of the enemy, a wounded soldier, Private Massey, of the Royal Fusiliers, who had taken shelter in a block-house. Several times they compelled to rest, but they persevered in bringing him to a place of safety. |

| The Royal Fusiliers | Private James Ashford | Private Ashford rendered Lieutenant Chase every assistance, and remained with him throughout. |

The error in the report of incorrectly recording Thomas Ashford as James Ashford was corrected in the London Gazette of February 7th, 1882 which carried the following:-

Erratum

The Christian name of Private Ashford, the Royal Fusiliers, upon whom Her Majesty has been graciously pleased to confer the decoration of the Victoria Cross, is Thomas, and not as stated in the Gazette of 7th October, 1881.

The presentation to Private Thomas Ashford took place on the island of Madras and was recorded in the Madras Mail and reproduced in the Bury and Norwich Post, and Suffolk Herald edition of January 17th, 1882.

Presentation of the Victoria Cross

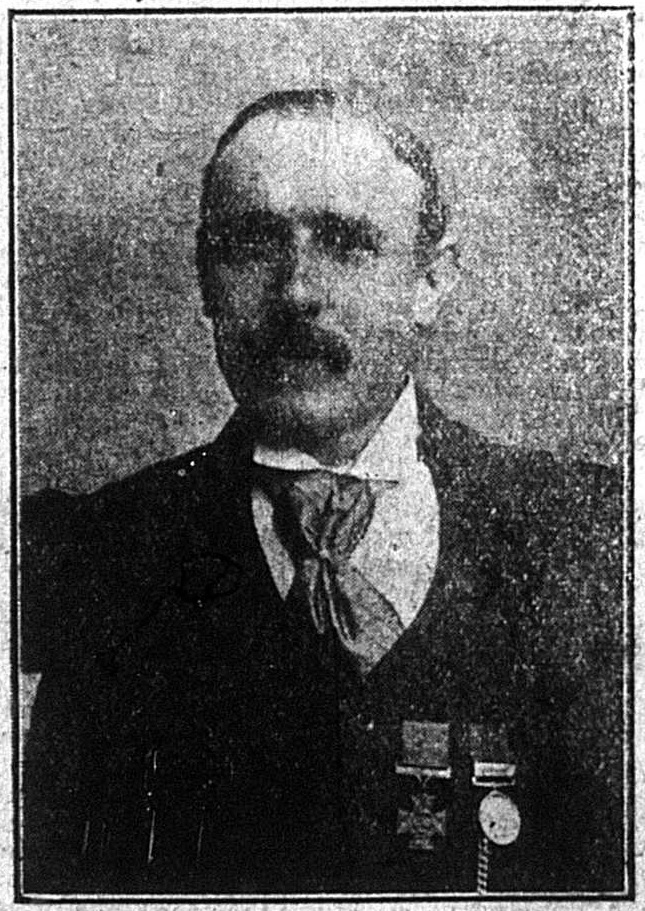

Our readers will be glad to learn that Private Thomas Ashford, of the Royal Fusiliers, the son of an old inhabitant of this town, has received the Victoria Cross for bravery in rescuing a wounded comrade at Deh Khoja, near Kandahar, during the late war in Afghanistan. The following account of the investiture is taken from the Madras Mail, of December 14th, 1881:-

One of the most brilliant military parades that Madras has seen for a long while was held yesterday evening, on the Island, on the occasion of the Victoria Cross being bestowed on Private Thomas Ashford, of the Royal Fusiliers, for conspicuous gallantry at Deh Khoja, when, in conjunction with Lieutenant Chase, of the Bombay Staff Corp, to whom the Victoria Cross has also been awarded, he rescued a wounded soldier of the same regiment named Massey. The scene yesterday reminded one of the time when the Birthday Review, in honour of Her Majesty the Queen, was held with all the military splendour that this city could command.

Dense masses of people crowded round the enclosure, and between 4,000 and 5,000 troops were brought together, and took up position in the following order from the left: – Two batteries of the Field Artillery, from St. Thomas’ Mount, the 12-8th and 19-9th Brigades, Royal Artillery; the Governor’s Body Guard; the detachment of the Royal Fusiliers; the Madras Volunteer Guards; and the 10th, 12th, 19th, 24th 36th, 39th Regiments, Native Infantry. The native regiments from Palaveram came in in the morning, and the two batteries of Field Artillery from the Mount at 3pm. The ground was kept by details from all the native regiments and by the 1st Cavalry. The Commander-in-Chief’s escort wearing Afghan loongias or turbans, a style of head-dress adopted since their campaign in Afghanistan. The arrival of his Excellency General Sir Frederick Roberts, V.C., the Commander-in-Chief, and his Excellency the Right Hon. M. E. Grant Duff, the Governor, precisely at half-past four o’clock, accompanied by his Highness the Maharajah of Vizianzgram, and by a numerous and brilliant staff, was announced by a salute of seventeen guns from the saluting battery, the guns being served by the Duke’s Own Volunteer Artillery. The cortege took up a position by the saluting flag for a few minutes, and then proceeded in procession to inspect the troops formed up in line, with the several hands massed behind. The procession, in addition to their Excellencies the Commander-in-Chief and the Governor, was composed of the following officers, who took position according to their respective rank: – Brigade-General Clark, Adjutant-General; Brigade-General O’Connell, Quarter-Master General; Brigade-General Stewart, Commanding Centre District; Colonel T. Dyer, Deputy-Adjutant General; Colonel Faunce, Assistant-Adjutant-General; Colonel Caine, Assistant-Adjutant-General Royal Artillery; Lieut-Colonel Ewing, Deputy-Quarter-Master General; Major Eyre, Deputy-Assistant-Quarter-Master General; Major Curtis, Deputy-Assistant-Adjutant-General; Subadar Major and Honorary Captain Mahomed Abboolah, Native Aide-de-Camp to the Commander-in-Chief; Subadar Major Hoossain Khan, Native Aide-de-Camp to the Governor and the Staff of his Excellency the Governor, &c.

The procession was followed by Mrs Grant Duff accompanied by Captain Bagot, A.D.C., in an evening carriage drawn by four horses with postilions. The procession passed down the line from left to right, and the troops presented arms, and the massed bands played. On reaching the left of the line, Sir Frederick Roberts galloped back to the Fusiliers whose flank companies were then wheeled forward, Private Ashford was then called to the front and his Excellency directed the Adjutant-General to read the General Order and warrant of appointment. His Excellency then dismounted and pinned the proud distinction upon the breast of Private Ashford, who is a native of Newmarket, and has been 4 ½ years in the Army, and who, we may now remark here, is 23 years of age. Then, remounting, the Commander-in-Chief thus addressed the hero of the day, and the Royal Fusiliers:

“If affords me great pleasure, Private Ashford, to present to you the Victoria Cross which Her Majesty has been graciously pleased to confer upon you. I am especially glad to have this opportunity of seeing the Royal Fusiliers, for I well know the hard work they had to do in Afghanistan, and how admirably they conducted themselves while there. I was not at Kandahar on the 16th August, 1880, but I heard from all that on that occasion the Battalion nobly maintained its high reputation. It must be very gratifying to your comrades to see you decorated in this public manner; my regret is that the whole of the Battalion could not be present. Those at Bellary will, however, hear that the parade was attended by his Excellency the Governor, and a large number of the principal residents of Madras, and it will, I am sure, be as pleasing to them as it is to us all that your gallant conduct should be thus specially recognised.”

Private Ashford, V.C., then, under orders, took his post at the saluting flag, and stood between the Commander-in-Chief and the Governor. The flank companies were then wheeled back, the Fusiliers formed quarter-column on the right company, and the whole force wheeled to the right, and proceeded to march past in column of double companies. Before reaching the first wheeling-point the infantry had to wade through a veritable pond, half-way up to the men’s knees, which, however, was only a preparation for the actual bog through which they had literally to plough their way, just at the critical moment opposite the saluting point. This quagmire no doubt seriously affected the steadiness and marching of the troops. The various brigades then halted, changed ranks, and marched past in mass of quarter-column, and changing ranks once more, again marched back in line of columns by brigades. The cavalry and artillery then trotted past, the infantry meanwhile taking up their old position in line of columns opposite the saluting flag. The whole division then advanced in review order, halted, presented arms, and having received the order to march to quarters, the bands struck up, and the review was over. The weather looked very threatening during the parade, and during the ceremony of the investiture a slight drizzle came on, which fortunately only lasted a few minutes. It was close upon six o’clock when the troops were dismissed. A second salute was fired from the saluting battery as the Commander-in-Chief and the Governor left the field.

In the issue the following week (January 24th) was the report:

“A portrait of Private Thomas Ashford, who recently received the Victoria Cross for bravery in rescuing a wounded comrade, under the circumstances detailed in last week’s paper, appeared in the ‘Illustrated London News’ on Saturday last.”

Lieutenant William St. Lucien Chase was invested with his Victoria Cross by the GOC Bombay at Poona, India on 23rd January 1882.

William Chase was born on the 2nd July 1856 at St Lucia, West Indies, eldest son of Captain R.H. Chase and Susan Ifill, daughter of John Buhott. He was educated privately and entered the Army in September 1875, being gazetted to Her Majesty’s 15th Foot. He did duty with the Headquarters of his regiment in India for two years, passed with distinction the necessary examinations, and was admitted to the Bombay Staff Corps.

In the Second Afghan War of 1878-1880, Chase served with the 28th Bombay Native Infantry, a constituent of the Kandahar Field Force. He was present with his regiment throughout the defence of Kandahar, and took part with the four companies in the ill-fated sortie to the village of Deh Khoja where the casualties of the regiment included Lt-Colonel Newport and thirty rank and file killed, and Lt-Colonel Nimmo and twenty rank and file wounded.

After the regiment had left Kandahar, Lieutenant Chase was given command of the Killa Abdulla Post until relieved in November 1880. In the following January, 1881, he was again sent to command the post of Gatai, on the lines of communication, and remained there until all the troops of the Kandahar Evacuating Force had passed through en route to India. In 1884 William Chase served in several campaigns and was continually mentioned in Despatches.

Colonel William Chase died, aged 51, on 24 June 1908 at Quetta, Baluchistan, India (now North West Pakistan) and is buried in The English Cemetery, Quetta Cemetery.

A brief history of the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross came into being on 29th January 1856 by Royal Warrant. It was, in part, an idea by Queen Victoria and others, including the Duke of Newcastle, who was, at the time, the Secretary of State for War, as a means of rewarding junior officers and other ranks in the army and navy for exceptional bravery in the face of the enemy. This award would ignore rank, long service, wounds or other circumstances apart from conspicuous bravery and could also be awarded by ballot in some cases.

The first occasion when it was distributed was at Hyde Park in June 1836, when Queen Victoria presented 61 crosses to a band of heroes of the Crimean War, forty-seven to the Army, twelve to the Navy and two to the Marines.

The design was purposefully not to be ornate, enameled or detailed. Bronze from two Russian cannon that had been captured at Sebastopol during the Crimea War was used to create the cross. Shaped as a ‘Maltese Cross’ it is 3.6 cm wide with the royal crest of Queen Victoria in the centre and a scroll with the motto. The original motto was suggested as ‘For the Brave’ but the final wording was to be ‘For Valour’. The cross was attached by a ‘V’ shaped link to a bar and ribbon, blue for the navy and dark red for the army. In 1920 this became a red ribbon for all services and was to be worn on the left breast. The reverse of the cross was to carry the date of the action and the name of the holder in capital letters.

In the original warrant, there was provision for the cross to be taken back, ‘Forfeiture’ if the holder later did any act considered to be in ‘wholly discreditable circumstances’ and there have been eight cases where this occurred. However, a Royal Warrant in 1920 changed the original ruling as King George V felt strongly that the award should never be taken away from anyone, even if the person was to ‘be sentenced to be hanged for murder’.

The award by election of ballot among comrades was used where a unit as a whole performed collective acts of heroism and no one person could be identified as outstanding. The number of awards issued would be dependent on the size of the unit.

William St. Lucien Chase was the 358th recipient of the Victoria Cross and Thomas Elsdon Ashford the 359th.

The original warrant of 1856 did not allow for awards to be given posthumously. This was changed in 1902 by King Edward VII when six officers and other ranks who fell prior to this date received the medal, with the first two being Coghill and Melvill who were killed trying to save the Queen’s Colour as they escaped the massacre at Isandhlwana in the Zulu War of 1879, medal numbers 360 and 361 respectively.

Thomas Elsdon Ashford’s Victoria Cross was presented to the Royal Fusiliers Museum in the Tower of London by bequest in 1992.

The family of William St. Lucien Chase handed over his V.C. medal group to the Army Museum of Western Australia, Fremantle, on Sunday 23rd November, 2003.

In 1882 Thomas was made a lance-corporal, but chose to revert back to a private a month later. Brian Best of Victoria Cross Society suggests that the reason for this was that he was suffering from syphilis at the time. When he requested to be made a private again rather than a lance-corporal, he was in hospital and being treated for syphilis.

Thomas was discharged to Class B Army Reserve on February 24th 1884 and left the Army on June 13th 1889. His conduct was described as “very good.”

Broomleys House

After leaving the army and returning home to England in 1884, Thomas originally took up farming in Hallaton near Harborough in Leicestershire but within a year had moved to Brook Street in Thringstone.

In 1881, Betsy Ann Sisson, Thomas’ wife to be, was working as one of three domestic servants, along with a cook and footman at Broom Leys House, working for William Whetstone, his wife and their seven children. William had inherited after his brother, Joseph Whetstone died in 1868. Joseph was the owner of both Whitwick and Ibstock collieries and in 1840 was the Lord Mayor of Leicester.

Thomas married Betsy Ann Sisson on 29th January 1891 at Thringstone St. Andrews Church when aged 30, listing his father Thomas as a boot maker and Betsy, aged 28, born in Coleorton and listing her father as William, a miner, originally from Nottinghamshire.

A few months later at the time of the census, Thomas and Betsy were boarders at the home of John and Zillah Abell on Brook Road, Thringstone where Thomas was listed as a labourer at the colliery.

Their first child, Lilian Minnie Ashford was christened on 20th November 1892 where Thomas was listed on the baptismal record as a collier and living on North Street, Whitwick.

On 31st October 1893 Thomas joined the Leicester Postal Service.

Their second child, Thomas Elsdon Ashford was christened on 8th April 1894 but died within a few months and was buried on 3rd June 1894.

Their third child, Gertrude Sophia Ashford was christened on 8th December 1895 and the family were now listed as living in Skinner’s Lane, Whitwick.

In 1900, the family had their fourth child, another son, who was christened on 8th December 1900, named Victor Charles Ashford, (surely no coincidence in having the initials V.C.) but again within a few months, their son had died and he was buried at Whitwick cemetery on 12th February 1901.

On the 1911 census, Lilian is recorded as a General Servant, Domestic, while her younger sister, Gertrude is recorded as a Drapery Apprentice.

Thomas worked for the Post Office as a Postman for over twenty years, covering twenty miles of the Grace Dieu route. Many commented on him being a popular, kind and unassuming man, who would rarely talk about his bravery and that on Sundays, when it was a familiar sight to see him wearing his Victoria Cross and Afghan medal, they were usually concealed under a jacket.

Thomas, his wife Betsy and their two daughters lived in Skinner’s Lane. There are several different numbers given as his address but it is considered that he originally lived at number six but this was changed to number three by the Post Office.

Skinner’s Lane is a very ancient lane that was first mentioned in the rates book of 1843, then in the directory of 1846 and also in the 1851 census. This lane was where the forest animal skins were dried before being taken to the tanneries at Coleorton. The remains of the old house where this occurred is now incorporated into the house that is number three Skinner’s Lane, which was a row of houses built in the 1800’s.

Skinners Lane

Coalville Times (Friday 21st February 1913)

V.C. Hero’s Death at Whitwick.

MR THOMAS ASHFORD

The death occurred about five o’clock this (Friday) morning at his home in Whitwick of Mr Thomas Ashford, V.C. who had for 20 years been a rural postman and was believed to be the only Victoria Cross hero in the postal service throughout the country. Ashford had suffered from an attack of bronchitis, through which he took his bed on Boxing Day and had been there ever since. He remained conscious to the last and, in the words of his wife to our representative this morning “died like a soldier”. He was 54 years of age and leaves a widow and two grown- up daughters.

Coalville Times (Friday February 28th 1913)

Whitwick V.C. Hero

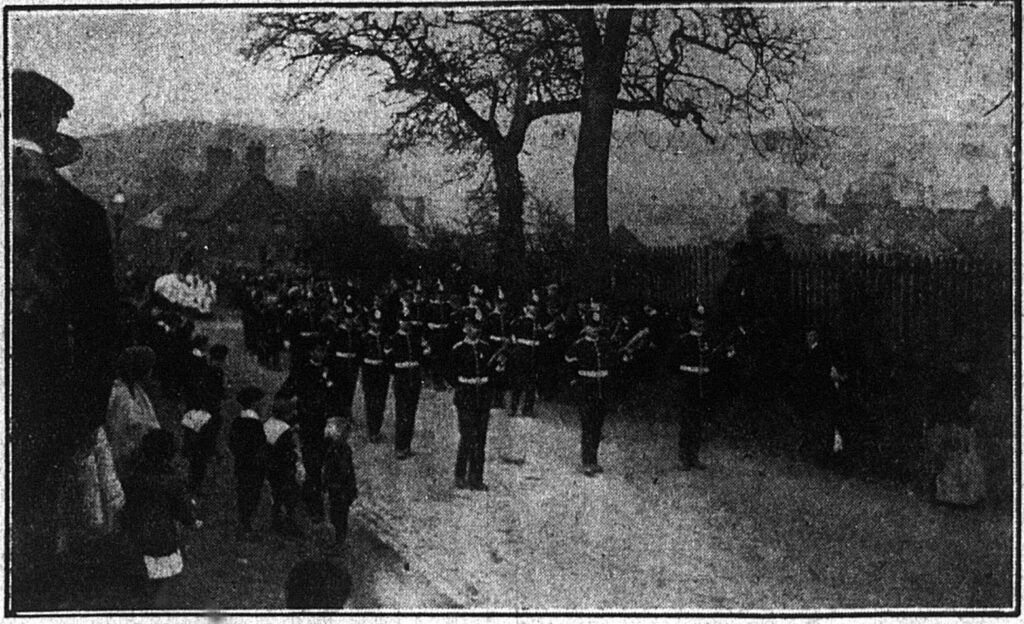

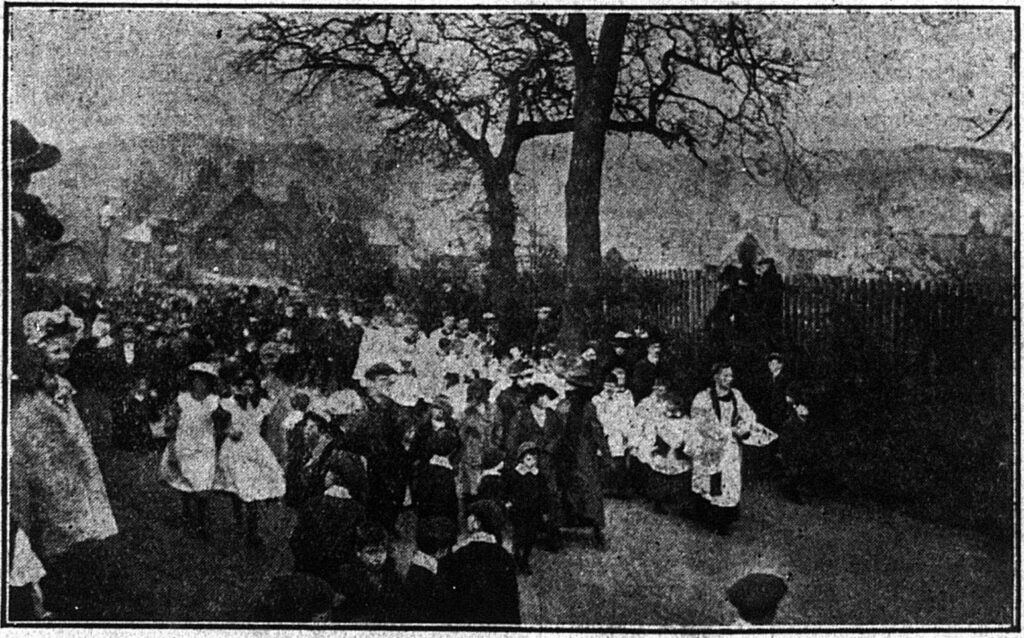

Huge crowd at the funeral

Interred with military honours

A vast concourse of people, estimated at about eight thousand, assembled at Whitwick on Tuesday afternoon, to witness the funeral of Mr Thomas Ashford, the V.C. postman, whose remains were laid in their last resting place amid remarkable scenes, testifying to the great respect in which the deceased was held and public admiration for the dead hero in connection with the brave deed which won for him the distinction so coveted of all military men.

Never has such a scene been witnessed in Whitwick as that on Tuesday afternoon. At practically all the shops and residences the blinds were drawn, and various sections of the military forces were represented in the funeral cortege, which must have numbered some hundreds of persons. The streets from Ashford’s humble cottage in Skinner’s Lane to the Parish Church, and onward to the cemetery were crowded with people so thickly as only to leave just sufficient room for the funeral cortege to pass.

As the body was brought out of the house and placed on an ambulance carriage, covered with the Union Jack, a party of about 20 men of the 17th Leicester Regiment from Glen Parva Barracks, under Sergeant Gamble, who had lined up in front of the house, presented arms, and then with reversed rifles, walked at the head of the procession.

The chief mourners were the widow and two daughters, Lily and Gertrude, Mr and Mrs Neale of Hallaton, brother-in-law and sister, Mr W Handford, brother-in-law of Highfields Coalville and Mrs Handford, Mr C Holmes, brother-in-law of Whitwick and the Messes Holmes (2), Mr and Mrs Hill of Hallaton and Mrs Harris and Miss Allgood of the Whitwick Post Office. Walking immediately after the widow and daughters were Sergeant-Major I Williams and Colour Sergeant W Perkins, from the Hounslow London depot of the Royal Fusiliers, the deceased’s regiment and others in the procession were representatives of the Leicestershire Imperial Yeomanry, including Captain Surgeon Burkitt (Whitwick), Sergeant-Major Parker, Sergeant-Major Peach and Major Diggle of Loughborough, with about 20 of the rank and file, fifteen members of the Hastings Company of the Leicestershire Territorial Regiment in command of Col-Sergeant Farmer, about 20 members of the National Reserve with Ex-Sergeant-Major Harris of the Yeomanry in charge.

Ashby, Coleorton and Whitwick Troops of Boy Scouts, in charge of Scoutmaster S Perry (Whitwick), Scoutmaster Ellison and Assistant Scoutmaster Thornley (Ashby), Sergeant-Instructor Stone of the Whitwick School of Arms, about fifty postmen, with the Coalville postmaster, Mr G Wallis, and Mr R H James, postal inspector of Leicester, representing the department. Drs J S Hamilton (Coalville) and J Archibald (Ellistown), Father O’Reilly, Mrs J J Sharp, who, it is not generally known, is the officially appointed “soldier’s friend” for the Whitwick district and others.

Twelve of the deceased’s postman comrades in uniform, acted as bearers, these being Messrs J H Timms, P H Haggar, H Laywood, C W Woods, H Ponntain, G H Kenney, and W Bailey (Coalville), T Harris (Whitwick), W Covell, A A Watson, R T Ridderford and G Keyworth (Leicester).

The 39th Psalm was sung, and after the reading of a portion of Scripture from the first epistle to the Corinthians, 15c, the Rev. C Shrewsbury said they were gathered there that day in such large numbers to do reverence: to pay their last act of homage to a brave and gallant soldier. There was no need for him to tell them, as they all knew of the heroism by which the deceased won that coveted distinction – the Victoria Cross. It was a far cry from that village in the centre of England, to the scorching glare of Afghanistan, but they tried to picture the brave deed of their departed brother, who, like a true British soldier, did not hesitate to risk his own life when the life of another was in peril. The Cross was won by that noble act of gallantry which would not allow a wounded soldier to perish, but they bore him away for 200 yards under the fire of the enemy, bore him slowly and carefully until they reached a place of safety. He asked them to think of that noble act of heroism and yet perhaps some of them faltered in carrying out the commonplace duties of life. But that was not so with him whom they now mourned. He who had won that cross “for valour” on the field of battle was content for 20 years or more to perform hard work, still in the service of his country, walking 17 miles day by day, without a murmur or complaint. He was one of whom they might say that he could be absolutely trusted. Think of the many secrets he must have carried locked up in that postman’s bag of his, but when one’s letters were placed in his charge he knew that they were quite safe. This two-fold idea of duty was not always easy to carry out. It was easy sometimes to rise to a supreme act of sacrifice, but it was not so easy to carry out one’s duty loyally year in and year out, and it was because the devotion to duty shown far away in Afghanistan was continued for so many years here in Whitwick, that they were there in such large numbers that day to pay their last act of reverence.

The deceased’s favourite hymn, 234 “O Paradise, O Paradise” was sung, and during the service, Mr R G West (organist) played the “Dead March” in “Saul”.

The procession was met outside the Church by the Whitwick Holy Cross Band, who had been got together at short notice, the men having been fetched out of the pit the same morning, and under Bandmaster W Egan, they played the Dead March on the way to the cemetery.

A tremendous crowd was at the cemetery to witness the last rites performed by the Rev C Shrewsbury, and at the close of the service, the hymn, “On the Resurrection Morning” was sung. The body was enclosed in an oak coffin bearing the inscription:

Thomas Elsdon Ashford V.C. – Died February 21st 1913 – Aged 54 years

Immediately on the conclusion of the burial service the 17th Leicesters presented arms, and then fired three volleys over the grave, after which the buglers sounded ‘The Last Post’.

Some beautiful floral tributes bore cards as follows:

From his affectionate wife, Lily and Gertie. Gone but not forgotten.

With the deepest sympathy of the postmen at Leicester

To dear Tom, from his sorrowing sister, Sophia. Although a hero, modest as a violet.

Like the laurel, green his memory will ever be. With deepest sympathy from Mr and Mrs Bourne and family.

The noble hero’s task is done: his fight has been fought, his battle won. May he rest in peace. From Mr and Mrs G F Burton, Apsley House, Whitwick.

With the sincere regret and sympathy of the employees of Gracedieu Manor.

With sincere sympathy from the C Squadron of the Leicestershire Yeomanry.

With deepest sympathy from George and Flo, and Eva Hill, Hallaton, to a dear friend.

With deepest sympathy from his comrades at Whitwick and Coalville Post Offices.

With loving sympathy from Omar and Sophie, Evan and Mary, and Jack and Fred.

In loving memory of our brave comrade. Gone to his last rally. From the members of ex-naval and military C.S.A. G.P.O. Leicester

With deepest sympathy form the members of the Sergeant’s Mess, the Royal Fusiliers, Hounslow Barracks.

With deepest sympathy from Mr and Mrs W Handford, Highfields, Coalville.

From the Right Hon. and Mrs C Booth, Gracedieu Manor.

On the return journey the Holy Cross Band played “The Minstrel Boy” and the military parties returned to their starting point, the Whitwick School of Arms, where, before they were dismissed, Dr. Burkitt thanked them for their attendance which, he said, showed that they appreciated the gallant act of their dead comrade. They could not all win the V.C. but every man could do something for the honour of his country.

The arrangements for the funeral, which was of a much larger scale than anticipated and passed off without a hitch, were carried out by a small committee consisting of Dr. Burkitt, Sergeant Green, Sergeant Stone, Mr George West and Mr H T Bastard (secretary).

Letter from Lord Roberts

Notice of Ashford’s death was brought to the notice of Lord Roberts by Mr A Jones of 37 Harrow Road, Leicester and Mr Jones received the following letter from his lordship which was handed to the widow on the day of the funeral.

Englemere, Ascot, Berks

24th February 1913

Dear Sir

I am very sorry to learn from your letter of the 21st inst, of the death of Mr Ashford. I well remember his great gallantry at Kandahar, and the pleasure it gave me to present him with the Victoria Cross, awarded to him by her late Majesty Queen Victoria.

Please tell Mrs Ashford how much I sympathise with her and her daughters in their sorrow.

Yours very truly

Roberts F.M.

Muffled Peal

A quarter-peal of Grandsire Triples, 1,260 changes, was rung at Whitwick on Sunday last in 50 minutes, with the bells muffled, as a mark of respect to the late Mr Thomas Ashford V.C. The bells were rung by Messrs H Pegg (treble), S W West, J Moore, F Middleton, H Partridge, B West, W Fern (conductor) and J Bonser (tenor).

The ‘Coalville Times’ on Friday 18th April reported on the probate on 5th April. “Mr Thomas Elsdon Ashford, of 3, Skinners Lane, Whitwick, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for conspicuous gallantry before Khandahar in 1880, and who died on February 21st last intestate, aged 54 years, left estate value for probate at £123. Letters of administration of his property have been granted to his widow, and her sureties for the due administration of the estate, as provided by law for the property of persons dying intestate, are Mr Joseph Ball, of Knighton Fields Road East, Leicester, and Mr Walter Baker, of Brunswick Road, Leicester.”

Legacy

Coalville Times (Friday, August 19th, 1960)

Now they Remember the Forgotten Hero

At a meeting of the Whitwick branch of the British Legion, on Monday, it was decided to further their attempts to get a memorial for the unmarked grave of the Afghan War V.C., the late Mr Thomas Ashford, former Whitwick postman, who died in 1913.

The secretary, Mr J. Stinson, drew the attention of members to “Mr Charnwood’s Diary” in last week’s issue of the Times in which it was first reported that 85 year old Mrs Nellie Harris, a former Whitwick postmistress, wished to trace the next of kin of the local hero. Mrs Harris has intimated that she was willing to pay for a suitable memorial but could not go ahead with its erection without the permission of relatives.

Mr Stinson recalled that the Branch went into the matter of erecting a memorial in 1956, which marked the centenary of the award of the first Victoria Cross, but it was found that before anything could be done the permission of the relatives had to be obtained. The Branch intended to erect a wooden inscribed cross on the grave and after some effort on the part of the Branch a descendant was traced to an address at Whissendine, Rutland.

Replying to a letter from the Branch in January 1957, this relative disclosed that the only blood relative was a grand-daughter with whom he had discussed the matter and it was felt the erection of a suitable memorial was a matter for the family. The letter stated that the family intended to do something in the very near future and the writer would be visiting Whitwick in the next three or four days, when he could contact Mr Stinson. “That is nearly four years ago and I am still awaiting that visit”, Mr Stinson remarked. Since the report in the Times he had been approached by members who had complained that it looked as if the Legion had done nothing about it and for that reason he had invited a Times reporter to the meeting.

Mr Stinson said he had seen Mrs Harris and she had requested that the Branch make further efforts to obtain the necessary permission and she would pay for the memorial. During a long discussion some members felt the Legion had done all they could and it was now up to the relatives to come forward. Others thought it was up to the general public in the district or the local council to do something. A few members could not understand why it had gone on so long before anything was done, but it was pointed out that Private Ashford died in 1913, not long before the First World War, and it was quite probable that the grand-daughter would not have known her grandfather and in any case did not live in the district.

It was eventually agreed that the secretary send a further letter to the relatives, enclosing copies of press cuttings, in an endeavour to speed the matter up.

However, the situation remained unchanged for a further thirty years, but finally the fight by the members of the Whitwick branch of the Royal British Legion was successful and reported in the Leicester Mercury at the time which stated:

‘Mr Joe Stinson (70) of Gracedieu Road, Whitwick, who has been spearheading the campaign, said “I first realised Thomas Ashford was in the Whitwick cemetery after reading a Post Office magazine article about him in 1956. I went to find his grave and discovered there was not a headstone on it. Since then I have been trying to get a headstone put up but nothing has happened.”

That was until early last year when the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers agreed to meet the cost of a headstone for the grave. Officials at North West Leicestershire District Council also agreed to waive the usual cemetery fees and the headstone was finally put up.

Mr Stinson said “I am extremely pleased this campaign has ended now. The VC is the highest honour in the forces and it is important there is something in the cemetery to mark the fact that a villager who won the award is buried there.”

Last year, in honour of Mr Ashford’s bravery, councillors on the district council agreed that three village roads on a new estate off Church Lane should be named after him. They are Thomas Road, Elsdon Close and Ashford Road.’

Sources

Newspapers, Photographs and Articles

Whitwick Historical Group

The Post Office Magazine 20th June 1956

Coalville Times – Various issues

North-West News – April 1990

Leicester Mercury – Various issues

Internet

Passage to India – Fusilier Museum

Broom Leys School website

Royal Fusiliers Recipients of the Victoria Cross (J.P. Kelleher, 2001)

The Afghan War – Garen Ewing

Books

Monuments to Courage (David Harvey, 1999)

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to Garen Ewing for allowing me the use of articles and photographs from his excellent website on the Afghan War.

Photograph of Thomas Elsdon Ashford’s Victoria Cross is included with the kind agreement of Colin Bowes-Crick, Major (Retired) of the City of London HQ RRF.

Researched and compiled by Andy Murby – Whitwick Historical Group member.